Chronic Khat Use and Psychotic Disorders a Review of the Literature and Future Prospects

- Research commodity

- Open Admission

- Published:

Khat use as risk cistron for psychotic disorders: A cross-sectional and instance-control study in Somalia

BMC Medicine volume 3, Article number:5 (2005) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Little is known about the prevalence of khat-induced psychotic disorders in East African countries, where the chewing of khat leaves is common. Its primary psycho-agile component cathinone produces effects similar to those of amphetamine. We aimed to explore the prevalence of psychotic disorders among the general population and the association between khat employ and psychotic symptoms.

Methods

In an epidemiological household assessment in the metropolis of Hargeisa, North-West Somalia, trained local interviewers screened four,854 randomly selected persons from among the general population for disability due to severe mental problems. The identified cases were interviewed based on a structured interview and compared to good for you matched controls. Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the items of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview and quantified with the Positive and Negative Symptoms Calibration. Statistical testing included Student's t-exam and ANOVA.

Results

Local interviewers constitute that rates of severe inability due to mental disorders were 8.4% amidst males (above the historic period of 12) and differed co-ordinate to state of war experiences (no war feel: 3.two%; civilian state of war survivors: viii.0%; ex-combatants: 15.9%). The clinical interview verified that in 83% of positive screening cases psychotic symptoms were the most prominent manifestations of psychiatric illness. On average, cases with psychotic symptoms had started to apply khat earlier in life than matched controls and had been using khat 8.vi years before positive symptoms emerged. In about cases with psychotic symptoms, a pattern of binge apply (> two 'bundles' per day) preceded the onset of psychotic symptoms, in contrast to controls of the same age. We found pregnant correlations between variables of khat consumption and clinical scales (0.35 to 0.50; p < 0.05), and between the age of onset of khat chewing and symptom onset (0.70; p <0.001).

Conclusion

Bear witness indicates a relationship between the consumption of khat and the onset of psychotic symptoms amid the male population, whereby not the khat intake per se simply rather early onset and excessive khat chewing seemed to exist related to psychotic symptoms. The khat problem must be addressed by means other than prohibition, given the widespread employ and its role in Somali culture.

Groundwork

The nowadays report investigated the relationship between psychotic symptoms and the abuse of khat in the Horn of Africa. The leaves of the khat shrub (catha edulis) are traditionally chewed in Arab countries, the Horn of Africa and Eastward Africa [1] and recently this habit has spread to Western countries including the Us [2]. Due to improved transportation facilities, khat consumption has substantially increased during recent decades. This is reflected in the almost recent consequence of the World Drug Study: in 2001 five countries reported an increment in khat use and none a decrease; in 2002 an increment was reported in iv, a subtract, again, in none [three]. Kalix (1996) [4] estimates that about 6 million individual portions are consumed each twenty-four hours worldwide. During our field work in the city of Hargeisa, North-West Somalia (Somaliland), where khat use is non restricted past law, we observed that current means of intake do non correspond to the documented traditional use in the region. The traditional way of consumption was socially highly regulated: adult males (more seldom females) would gather and chew khat together at a so-called 'khat party', usually on weekends and afternoons until the time of the evening prayer [5, half dozen]. Reverse to this formerly restricted apply, current habits involve use by adolescents, chewing khat in tea-shops that operate 24-hour interval and night, early on morning time apply, as well every bit "binging" and "speed runs" that may last for more than 24 hours. Our study was based on observations by social workers of collaborating not-governmental organizations and by our team during field studies on war-related trauma. It was shown that the widespread utilise of khat is related to the large number of individuals with visible signs of psychosis who are either homeless or kept in hiding, e.g. in physical chains, past family members who afraid to expose them to the general public.

The main psycho-active component of khat leaves is cathinone (S(-)alpha-aminopropiophenone) [7]. Cathinone resembles amphetamine in chemical structure and affects the central and peripheral nervous organization [8, 9] and behavior [10, 11] similarly. Amphetamines and some of its derivatives take been shown to induce psychotic symptoms in experimental settings in humans [12, xiii] and animals [14] and have been known to exacerbate psychotic states in psychiatric patients [15, 16]. Similarly, khat-induced psychotic states have been described in several case studies [17–20]. However, the number of group, community and population-based studies on khat utilise and psychiatric symptoms [21–23] is still limited. Despite the ongoing scientific debate about amphetamine-induced psychosis it remains unclear whether the use of amphetamine-like substances including khat may actually cause a psychotic disorder in an otherwise salubrious individual, or trigger the onset of schizophrenia in an individual with high vulnerability to the affliction [24, 25]. The fact that presumed amphetamine psychoses practice non fully remit within weeks of abstinence in a substantial per centum of individuals [26] may also advise that those individuals really had a amphetamine-triggered schizophrenia. Increased drug use among psychotic patients may likewise come from an endeavor to annul nonspecific physical symptoms or side furnishings of neuroleptics [27].

The offset goal of this study was to verify the impression of an unusually high prevalence of psychotic disorders in the city of Hargeisa via an epidemiological survey carried out in a representative sample of households. In addition, we wished to report the association between khat abuse and psychotic disorders. If khat abuse does induce psychotic disorders, a college prevalence of psychotic diagnoses, mainly in men (as women rarely consume khat), was to be expected in Hargeisa compared to localities with less khat utilise. In addition, a instance-control study served to examine whether individuals identified in the survey suffering from psychotic symptoms presented a pattern of khat consumption different from matched controls.

Methods

Sample

In order to screen for households with mentally ill members, 612 households with iv,854 members were randomly selected every bit representative of the city of Hargeisa (approximately 400,000 inhabitants). For household selection the town was first subdivided into 30 sections of approximately equal populations. For this purpose we used the same sections as UNICEF in their assessment of vaccination coverage for children in Oct 2002, which were defined in a joint approach by UNICEF and the municipality of Hargeisa. A section had to be subdivided into square-shaped clusters if it was L-shaped, had a natural purlieus within its limits (e.g. a steep hill) or had a much greater length than depth. A map for each section or cluster was produced using an aerial photograph. For random selection the geographical center of each cluster was determined and a random direction was chosen using a compass, a watch and a list of random numbers between ane and 12 (a lookout was oriented according to the compass, whereby 12 o'clock was adjusted to North; the random number divers the direction according to the hours on the face up of the clock). Post-obit the random management until the border of the cluster was reached, all houses on the correct side within a range of 15 meters were numbered. The commencement household to exist approached was selected by a second set up of random numbers. The next houses were selected by door-to-door distance until the predefined number was reached. Trained local staff interviewed the heads of the 612 households. If the head of household was not bachelor, another adult fellow member of the household was asked to reply to the questions. If no household member could be interviewed, the next house was selected co-ordinate to the selection procedure.

The following question was used to determine whether a person severely disabled due to mental health problems resided in the household: "Are in that location any members of your household who currently have mental problems that are and then severe that the person has been unable to provide income or has been unable to help in the household for at least four weeks?" This criterion was fulfilled for 169 (137 male, 32 female) cases. These individuals will be referred to as 'positive screening cases'. A subsample of 52 'positive screening cases' was then randomly selected and examined in a clinical interview. In this group there were 44 males and 8 females. These individuals volition be referred to as 'examined cases'.

For each 'examined case' a matched control, who did not meet the criteria for disability due to mental health problems, was identified. Controls were matched by gender, age, and educational level. These 'case controls' were subjected to the same clinical interview every bit the examined cases. Forty-nine of the 52 examined cases and ane control were diagnosed with psychiatric or neurological disorders (on this basis we estimated a sensitivity of 0.98 and a specificity of 0.94 for the screening procedure). Nosotros included only those forty-three examined cases (82.vii%) in the further analysis who – in addition to the damage of function – showed as chief manifestations of mental bug at least ane very severe or two moderate positive psychotic symptoms in the absence of organic somatic damages that might explicate them; from hereon these are termed 'cases with psychotic symptoms'. The disorders of other examined cases were stroke (2), traumatic brain injury (ane), mental retardation (ii), and dementia (1). The instance command with a positive diagnosis reported hallucinations with intact reality testing during khat intoxication and was replaced by a healthy individual. Socio-demographic characteristics for the 2 studied groups are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Procedures and materials

All interviews were carried out in October and November 2002. Prior to the interview, participants were informed virtually the background of the report and the survey procedure. All participants signed a written informed consent, which was first read and explained to them (as most of the participants were illiterate). In the example of mentally challenged participants, background and process were also explained to the responsible caretakers whose written informed consent was a prerequisite for their participation. Interviews were approved by the local regime and the National Demobilization Commission of Somaliland. Representatives of the different communities were informed and invited to observe the assessment in the field. Paper advertisements, daily radio programs and flyers informed the population about and helped them to understand the real purpose of the assessment (at get-go rumors had spread that the research team would provide free medication for mentally disturbed individuals and created unreal expectations). Consequently, the level of cooperation was extremely loftier. Out of 73 households approached under the supervision of the start author just three refused their participation. Therefore, nosotros guess that in total less than 5% of all households refused participation.

Local interviewers were recruited among NGO and hospital staff who already had experience in working with mentally disabled persons. They participated in a two-week training course, which involved didactics the bones psychiatric concepts (due east.g. psychotic symptoms), interviewing skills, training on the screening-instrument and field work under shut supervision of experts. Later on the end of the class, fourteen of the seventeen trainees were employed for the duration of the study. Five interviewer teams, each comprising one male and one female interviewer, and iv local supervisors did the field work. The local supervisors received additional grooming on the random sampling method. During the starting time weeks of interviewing the first author closely supervised the teams in the field.

The screening interview assessed private socio-demographic information, khat consumption and experiences in the ceremonious state of war (subjects were grouped as either active state of war participants, noncombatant war survivors, or without any war experiences). Khat consumption (number of bundles/week) was assessed for the week prior to the interview. The household economic situation was approximated equally the sum of four significant assets (water tap, electrical power, Television set set, car) and type of housing (Table one).

Clinical interviews were carried out by some of the authors (MO, MS, CC, BL), all trained in the assessment of psychotic disorders and PANSS rating. Socio-demographic data and war-history were detailed. A standard result list was used to quantify the number of traumatic consequence types a person had experienced; the list included xi types of events: active combat experience, accident, natural disaster, witness murder or killing, rape, sexual molestation, physical assault, being kidnapped or captured, torture, other, or suffered shock because a close person had experienced a traumatic issue. In a brusque semi-structured qualitative interview the main areas of psychological condition and functioning were assessed. Additionally, psychotic symptoms were assessed using the items of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), Section One thousand [28]. The individual'south historic period at which the family first noticed positive psychotic symptoms that prevailed over six months was taken equally indication of the onset of a psychotic disorder. Khat consumption (average number of bundles/day) was assessed for the week earlier the interview and for the calendar week prior to the onset of symptoms in examined cases. Instance controls were asked about consumption in the week prior to the interview and for consumption at the age of symptom onset reported past his/her examined instance-pair (Table ii). As many examined cases were not able to give valid information, the principal care taker and other family members were besides interviewed.

Clinical interviews were administered in the English language with the help of trained local interpreters, who had participated in the same training course as the interviewers. Later on the interview, the interviewing psychologist rated the current psychopathology using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, PANSS [29].

All items of the standardized interviews were translated from English into Af Somali by mixed teams of clinical experts and bilingual staff. Several steps of independent back-translations and corrections were necessary until a satisfactory translation was achieved. Content validity was assured past the interest of clinical experts at all levels of the translation process. Besides, interpreters were introduced to the concepts targeted by the corresponding questions.

Data analysis

Differences between cases and controls were confirmed using chiii-tests (or Fisher's verbal tests), binomial testing, Educatee's t-test or Wilcoxon, and ANOVA or Krsucal-Wallis test (all tests two-tailed). Univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to explore the effects of war-trauma on the khat intake. Means and standard deviations are reported.

Results

Of the sample of 4,584 inhabitants of Hargeisa the screening interview disclosed 169 positive screening cases (i.e. iii.5%). Positive screening cases were more often male person than female (133 of one,581 men, i.e. 8.4%, and thirty of one,600 women in a higher place the age of twelve years, i.e. 1.9%; p < 0.001; Tabular array 1). Khat chewing was more frequent amid male positive than amidst negative screening cases above the age of 12 years: 46.6% of the 133 positive screening cases had chewed khat in the calendar week before the interview in contrast to 29.nine% of the 1,448 negative screening cases (p < 0.001). Consumers among positive screening cases had also chewed a greater amount of khat in the calendar week preceding the interview (positive screening cases: 4.1 ± 6.3 bundles; negative screening cases: 2.2 ± iv.0 bundles; p = 0.001).

The proportion of positive screening cases was essentially higher amidst males above the age of 12 who had agile war experience (ex-combatants) than in male civilian war survivors of the same historic period (p < 0.001, Table one). The latter proportion was significantly higher than in men without any war experience (p = 0.007).

Psychotic symptoms meeting our criteria were adamant for 83% (43) of the examined cases. Retrospective investigation suggested that the onset of psychotic signs occurred at the age of 23.iv ± nine.9 years (Due north = 38 men: 24.i ± ix.8 years; North = v women: 18.iv ± nine.6 years; p = 0.230).

PANSS ratings of these 43 cases showed a essentially higher magnitude of electric current psychotic symptoms compared to a sample of 240 medicated schizophrenic patients [30] in the post-obit subscales: Positive 27.one ± seven.3, Negative 32.0 ± 8.9, Composite -4.9 ± 10.6, General Psychopathology 52.7 ± 12.7, Anergia 16.6 ± v.5, Thought Disturbance 16.4 ± five.3, Activation 7.8 ± three.0, Paranoia/Belligerance 10.8 ± four.ane, Depression 9.v ± three.9, and Supplemental Calibration 17.4 ± seven.4. In farther exploratory observations, we noticed a high tendency towards aggressive and hyperactive behavior. During interviews, most patients reported that they were in contact with a ghost ('djin'), oftentimes associated with auditory, visual and somatosensory hallucinations.

Fifteen of the 43 cases with psychotic symptoms (35%) were under current medication at the time of assessment; another nine (21%) had received medication in the past. A diverseness of drugs had been given, ranging from neuroleptics (12 patients) to prometazine (6), benzodiazepines (3), tricyclic antidepressants (3), carbamazepine (1) and other unknown drugs (ten).

Uncontrollable (disruptive, violent) behavior had led to restraint of cases with psychotic symptoms by chaining them to an object in 28 of the 38 men (i.e. 74%) and three of the five women (i.eastward. 60%) (p = 0.608). Additionally, 9 men (24%) and 3 women (60%) had been locked up to control their behavior (p = 0.589). On boilerplate, the 31 cases with psychotic symptoms who had ever been chained had spent four.2 ± five.two years in chains (men: iv.5 ± 5.iv years; women: 1.8 ± ane.9 years; p = 0.410) and the 10 cases who had ever been locked up spent on average additional 5.2 ± 6.5 years restrained (men: 4.0 ± 6.six years; women: 10.0 ± four.2 years; p = 0.264).

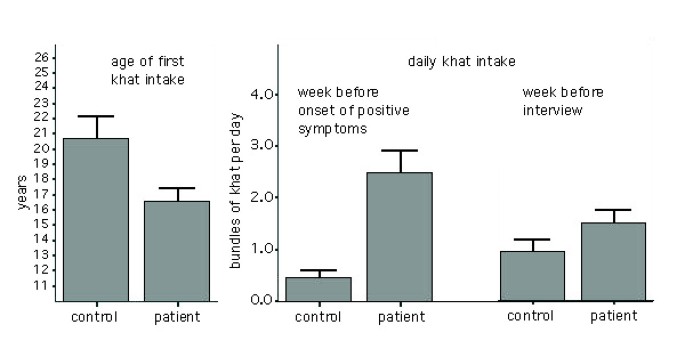

The proportion of khat user was higher among cases with psychotic symptoms than amid matched controls: all except one of the 38 male person psychotic cases, in dissimilarity to 25 of the 38 male controls, had used khat (p < 0.001). In the cases with psychotic symptoms, regular khat consumption had started at an earlier historic period (16.half-dozen ± 4.8 years) than among their matched controls (xx.vii ± 7.0 years, p = 0.010; Figure two). All except ane instance with psychotic symptoms (compared to 61% of controls, i.e. xiv of 23) had started to chew earlier the age of 23 years (p = 0.004). None of the women admitted to having always chewed.

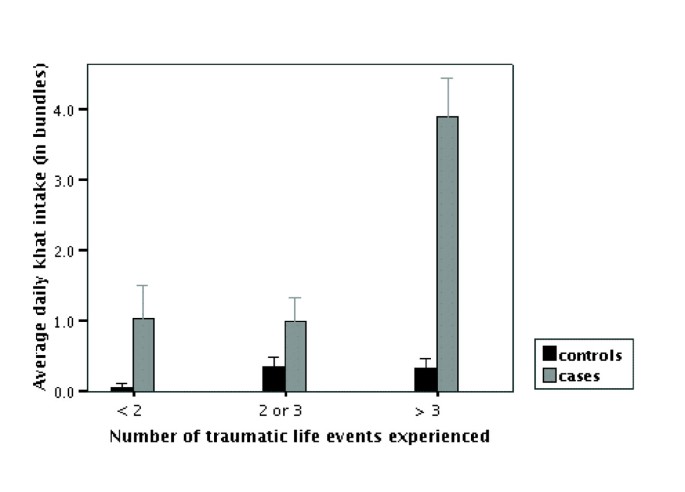

Khat intake and traumatic experiences. Average daily khat intake in bundles (at the age when the instance with psychotic symptoms showed onset of symptoms) according to number of traumatic life events. We divided the cases with psychotic symptoms and case controls into three groups co-ordinate to the number of upshot types experienced as follows: none or ane: 11 cases and 13 controls; two or three: 9 cases and 15 controls; more than three: 11 cases and 14 controls. Bars indicate hateful and standard mistake.

In the weeks preceding the onset of psychotic symptoms, cases with psychotic symptoms had chewed an average of two.5 ± 2.0 bundles/twenty-four hours compared to 0.5 ± 0.6 bundles/twenty-four hours in controls (p < 0.001; Effigy one). Excessive khat intake (> ii bundles/day) in this menstruation was found in 78% of chewers amidst male cases with psychotic symptoms (i.e. 29 of 37) but in only 4% of chewers amidst controls (i.due east. 1 of 25; p < 0.001). For the cases with psychotic symptoms, the historic period of onset of khat chewing correlated significantly with symptom onset (r = 0.70, p < 0.001). The lapse of time between first use of khat and onset of symptoms was greater than one yr in 31 of the 38 male cases with psychotic symptoms (i.due east. 82%); it varied around a mean of 8.half-dozen ± vi.6 years (median vii yrs). In the week before the interview 54% of the lifetime khat chewers among male cases with psychotic symptoms (i.due east. xx of 37) and 36% of the controls (i.e. ix of 25) had chewed khat (p = 0.162). Furthermore, psychotic patients consumed an average of 1.5 ± 1.0 bundles/24-hour interval, with controls consuming an average of 0.9 ± 0.vii (p = 0.172; Figure 1).

Patterns of khat consumption. Left: age of kickoff khat intake amidst lifetime chewers in patients with psychotic symptoms (35) and case controls (23); correct: amount of khat use (in 'bundles' per mean solar day) in the week before the onset of first positive symptoms (25 cases with psychotic symptoms, 24 controls) and in the week before the clinical interview (16 cases with psychotic symptoms, nine controls). Bars indicate mean and standard error.

Khat use correlated with severity of symptoms: In cases with psychotic symptoms onset of khat use correlated significantly with higher scores on the PANSS subscales Negative Symptoms (r = - 0.36, p = 0.039, N = 34), General Psychopathology (r = - 0.44, p = 0.009; N = 34), Anergia (r = - 0.39, p = 0.022, N = 34) and Thought Disorder (r = - 0.42, p = 0.014, North = 34), while the corporeality of khat consumed prior to onset of psychotic symptoms correlated significantly with the subscale Paranoia/Belligerence (r = 0.49, p = 0.006, N = 30) and the Supplemental calibration (r = 0.50, p = 0.005, N = xxx). The amount of khat consumed in the week before the interview correlated with the PANSS subscale Anergia (r = - 0.35, p= 0.029, North = 38).

The number of traumatic issue types experienced did non differ between cases with psychotic symptoms and matched controls (cases with psychotic symptoms: 3.1 ± 2.three events; matched controls: 2.9 ± two.4 events; p = 0.749). Also, the age when the first traumatic event was experienced did not differ between them (cases with psychotic symptoms: 20.2 ± 9.6 years; matched controls: xx.half dozen ± 9.2 years; p = 0.853). In order to judge the relationship betwixt number of experienced traumatic events and khat intake we used univariate ANOVA with khat intake earlier onset of psychotic symptoms (for controls at the historic period of symptom onset of matched pair) every bit dependent variable, and number of traumatic events in three categories (no or one consequence, two or three, four or more) and being a case or a command as independent variable. We establish significant effects for the number of traumatic events (Sum of squares 36.6; df 2; F = 17.028; p < 0.001) and for the variable 'case or control' (Sum of squares 53.nine; df 1; F = l.136; p. < 0.001) and a significant issue of their interaction (Sum of squares 31.0; df 2; F = fourteen.404; p < 0.001) (total Rii = 0.620). In Figure 2 the results are displayed graphically.

Discussion

The present study revealed a number of interesting and relevant findings.

- (i)

In a representative subsample of male person inhabitants of Hargeisa (older than 12 years) we establish 8.iv% severely disabled due to mental bug; of these, 83% had severe psychotic symptoms. Compared to the prevalence rates of psychotic disorders reported for male person samples elsewhere [31, 32] this is higher than expected. Furthermore the gender ratio among the mostly psychotic positive screening cases was unusual (1 women to seven.7 men).

- (ii)

Khat abuse showed a significantly earlier onset and was more often excessive in male cases displaying psychotic symptoms than in matched controls.

- (iii)

At that place is a higher vulnerability to inability due to mental disorders in those groups of gild who were directly involved in combat in the past.

- (4)

Among the positive screening cases examined and their matched controls we plant that khat intake before the onset of psychotic symptoms (respectively at the same historic period for matched controls) was college when more traumatic events had previously been experienced.

These results are intriguing, as we may have detected just the very tip of the iceberg with our sub-optimal screening process, leaving less severe cases of mental and neurological disorders undiscovered.

The findings of the present study propose that there is an association betwixt khat consumption and psychosis; however the existence of a causative relationship and its direction between the 2 remains unclear. Furthermore, it seems that it is not the consumption of khat per se only rather specific patterns of information technology that are related to psychosis, particularly early onset in life and the excessive intake (> two bundles per day). Both seem to be related to active participation in war, east.g. child ex-combatants used khat while fighting in social club to counteract fear and enhance operation [33]. Excessive khat consumption has already been reported to exist associated with higher severity of psychiatric symptoms [21]. Our data likewise suggest that there might exist a moderating effect of the number of traumatic experiences on subsequent khat intake. This would be in line with the cocky-medication hypothesis.

Khat consumption might be related to the outbreak of psychosis in various means. Considering psychoses as the result of genetic and acquired vulnerability and additional stress factors, the early onset of khat abuse may take substantially increased the risk in already vulnerable individuals. In animal studies, impairment imposed on the developing brain, e.thousand. past drugs, increases the potential of amphetamine-similar agents to change neuro-chemic systems and to induce psychotic-like beliefs [34]. In humans, drug corruption during puberty has been constitute to precede the onset of psychotic symptoms and prodromi [35] and to be related to poorer handling upshot [36]. Additional hazard factors and particular stressors, such as war experiences, may contribute to an increased vulnerability. It is shortly unclear, however, whether traumatic experiences human activity indirectly through higher drug consumption in traumatized men or whether they exert a directly outcome on the brain, increasing the run a risk of developing psychosis. The temporarily higher khat abuse preceding showtime symptoms in cases with psychotic symptoms compared to example-controls may suggest that khat consumption is the primary agent, causing the onset of psychoses. This assumption is further strengthened past the inequality in the gender ratio, as women are more often than not denied admission to the drug.

Moreover, khat consumption may affect the course of a psychotic disorder and the maintenance of symptoms. In contrast to the high khat consumption prior to the onset of psychotic symptoms, the amount of electric current khat consumption did not differ betwixt cases with psychotic symptoms and controls and a significant number of patients did not take current access to the drug. Drug-effects on the course of affliction may be attributed to sensitization [37] or to lasting neurotoxic effects of prolonged stimulant intake [14]. To clarify the question of how continued khat consumption might affect the further evolution of psychotic symptoms, the number of relapses related to khat intake would be of tremendous importance. Our observation was that once a patient has developed severe psychotic symptoms he is restrained (due east.g. chained) and kept away from the drug until symptoms remit. However, every bit before long as he is released the patient engages again in (often excessive) khat consumption until symptoms relapse and he is restrained again. Many patients had lived through this circle several times. In Western samples of amphetamine-induced psychosis, first relapses have mostly been studied [37]. Furthermore, it seems plausible that the conditions under which cases with psychotic symptoms were frequently kept may have infuenced the grade of any psychopathological development.

Some methodological shortcomings of the written report are related to the nature of field work in this specific post-conflict setting, which involved restricted freedom of movement due to the security situation and limited resources. All the same, although a perfect design is non possible in a rather complex field situation, the importance of such studies is evident from the fact that trivial or no data from post-state of war Somalia is bachelor. Offset, we could not control whether our sample was comparable to the population from which it was drawn due to the lack of recent statistics in Somalia.

Second, the validity of our screening and clinical interview can be questioned considering of diverse points, due east.g. whether the descriptions of symptoms and disability might be adequate for the Somali culture, or whether factors such as estimation or the interviewing of a whole family unit rather than a single patient might distort the information. In our approach we decided to use disability as a selection criterion and a descriptive rather than a normative arroyo to place the reasons for it. Thus, we decided to use the more than unspecific terms 'cases with psychotic symptoms' or 'psychotic symptoms' rather than 'schizophrenia' or 'drug-induced psychosis'. However, the fact that our local interviewers found 123 of the 169 positive screening cases (72.8%) restrained, i.e. chained or locked upward, and the overall loftier average PANSS scores of the examined cases, prove that at that place are 'hard' criteria, which justify the apply of the term 'psychosis' and validate our screening. Nevertheless, nosotros recognize that with our method we must have failed to discover persons suffering from psychotic and other mental disorders (false positives). But assuming that this error is somehow the same for the whole sample, our finding that the grouping of order that engages most in khat chewing (males higher up the age of 12) nearly often suffers severe impairment due to mental disorders shows evidence that khat is related to mental health problems.

Thirdly, the fact that nosotros could not choose our matched controls from the pool of negative screening cases – the resources that would have been necessary to (repeatedly) contact and arrange appointments with them exceeded our capacities – leads without any doubt to an overestimation of the specifity of our detection procedure.

Furthermore, the retrospective third-person assessment of the onset of psychotic signs, as well equally the retrospective and subjective assessment of khat employ, will accept introduced some error variance in the data. Nevertheless, nosotros believe that especially in the Somali culture khat intake cannot be compared to whatever food intake, of which the retrospective assessment is problematic. In the Somali civilisation khat has a special significance, which also comes from existing traditional knowledge near its dangers. Therefore we suppose that retrospective assessment of khat intake is more valid than that of food intake. Also, the furnishings of social desirability might have affected both the detection of positive screening cases and the cess of khat employ. The fact that dozens of families approached the chemical compound of our collaborating partner agencies in order to find help for their mentally sick members (often they brought them in bondage to the compound) shows the great need for mental health services. Thus, the tendency to hibernate family members from our interviewer teams tin be estimated as marginal. On the contrary, during the interviews our greater fear was that households would over-written report the presence of mentally challenged family members. For this reason, we counted only those persons every bit positive screening cases when their existence in the household could be validated (e.chiliad. by their physical presence). The cess of khat consumption is another bespeak where effects of social desirability tin exist causeless. Whereas the information given past examined cases could be validated past the information of family members, nosotros were well enlightened of the danger that the matched controls might take under-reported their khat intake. In order to let for this in the interview we spent much time and effort to place the existent khat intake (e.m. ofttimes we had to 'negotiate' about the answer to the khat questions – a habit inherent in Somali culture). All the same, the loftier correlations validate the assessment procedures.

Besides, the sample size was besides modest to reply some of the questions in detail, especially the small number of female examined cases. Nevertheless, the results were nonetheless statistically very robust.

In sum, our pattern could not make up one's mind the existence of a causal relationship between khat and psychosis – this would have been also ambitious a goal. Nevertheless, our main findings do non contradict the hypothesis that khat might cause psychosis.

Future enquiry should focus on the question of causality. Unfortunately, the Horn of Africa is probably the region where stimulant abuse currently reaches highest levels on a world-wide scale. This circumstance offers a unique inquiry opportunity for cross-exclusive and repeated measurement studies, which would enable us better to empathise the relationship between schizophrenia and drug furnishings and to fill the gap in knowledge related to khat use. At the same time, the alarmingly high prevalence of khat chewing among persons who suffer from psychotic symptoms in 1 of the countries of its highest use, and the magnitude of man suffering associated with it, demands the development of adequate community-based prevention and treatment interventions. The usefulness of standard procedures derived from adult countries and brought to the Horn of Africa must exist viewed in a "service-enquiry attitude"[38]. We believe that khat abuse has become a tragic obstruction for the reconstruction of this state of war-torn social club; consequently, there is an urgent need to address this mental health upshot with means other than prohibition and regulation of the need side through taxation, as khat is integral to the Somali culture.

Determination

Non khat intake per se but rather specific patterns of it are linked to the development of psychotic symptoms, like early onset in life, excessive chewing (> 2 bundles/day) and use as self-medication for war trauma related symptoms. Although nosotros cannot found a causal relationship between khat and psychosis, nosotros find some show that the prevalence of psychotic disorders is increased among the male adult population of Hargeisa. Ex-combatants are the group in club who are nigh afflicted past severe mental disorders, among them we find the highest abuse of khat. The way of khat use in Hargeisa is changing, indicated by e.g. the development of a group of heavy users who evidence consumption patterns similar to amphetamine addicts in Western countries. Measures of prevention and treatment of and further research on khat-related severe mental disorders take to be undertaken, however, taking into consideration that khat is an integral role of the Somali culture, which cannot simply exist prohibited.

References

-

Halbach H: Medical aspects of the chewing of khat leaves. Bull Globe Health Organ. 1972, 47: 21-9.

-

Gegax TT: Run into the khat-heads. Newsweek. 2002, 140: 35.

-

UNODC: World Drug Report 2004. 2004, Vienna: Un Office on Drugs and Criminal offence

-

Kalix P: Catha edulis, a plant that has amphetamine effects. Pharm World Sci. 1996, 18: 69-73. 10.1007/BF00579708.

-

Elmi Every bit: The chewing of khat in Somalia. J Ethnopharmacol. 1983, 8: 163-76. 10.1016/0378-8741(83)90052-one.

-

Kennedy JG, Teague J, Fairbanks L: Qat use in North Yemen and the problem of addiction: a study in medical anthropology. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1980, 4: 311-44. 10.1007/BF00051810.

-

Szendrei K: The chemistry of khat. Bull Narc. 1980, 32: 5-35.

-

Kalix P: Pharmacological properties of the stimulant khat. Pharmacol Ther. 1990, 48: 397-416. 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90057-ix.

-

Nencini P, Ahmed AM: Khat consumption: a pharmacological review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1989, 23: 19-29. 10.1016/0376-8716(89)90029-Ten.

-

Zelger JL, Schorno HX, Carlini EA: Behavioural effects of cathinone, an amine obtained from Catha edulis Forsk.: comparisons with amphetamine, norpseudoephedrine, apomorphine and nomifensine. Bull Narc. 1980, 32: 67-81.

-

Woolverton WL, Johanson CE: Preference in rhesus monkeys given a choice between cocaine and d, l-cathinone. J Exp Anal Behav. 1984, 41: 35-43.

-

Bell DS: The experimental reproduction of amphetamine psychosis. Curvation Gen Psychiatry. 1973, 29: 35-40.

-

Griffith JD, Cavanaugh J, Held J, Oates JA: Dextroamphetamine. Evaluation of psychomimetic properties in human. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972, 26: 97-100.

-

Robinson TE, Becker JB: Indelible changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration: a review and evaluation of animate being models of amphetamine psychosis. Brain Res. 1986, 396: 157-98.

-

Angrist B, Rotrosen J, Gershon S: Differential effects of amphetamine and neuroleptics on negative vs. positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1980, 72: 17-nine. ten.1007/BF00433802.

-

Janowsky DS, Davis JM: Methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, and levamfetamine. Effects on schizophrenic symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976, 33: 304-8.

-

Pantelis C, Hindler CG, Taylor JC: Use and corruption of khat (Catha edulis): a review of the distribution, pharmacology, side furnishings and a clarification of psychosis attributed to khat chewing. Psychol Med. 1989, 19: 657-68.

-

Yousef G, Huq Z, Lambert T: Khat chewing as a cause of psychosis. Br J Hosp Med. 1995, 54: 322-6.

-

Jager Ad, Sireling L: Natural history of Khat psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1994, 28: 331-2.

-

Alem A, Shibre T: Khat induced psychosis and its medico-legal implication: a case study. Ethiop Med J. 1997, 35: 137-9.

-

Dhadphale 1000, Omolo OE: Psychiatric morbidity amongst khat chewers. East Afr Med J. 1988, 65: 355-9.

-

Bhui K, Abdi A, Abdi M, Pereira Southward, Dualeh M, Robertson D, Sathyamoorthy 1000, Ismail H: Traumatic events, migration characteristics and psychiatric symptoms among Somali refugees – preliminary communication. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003, 38: 35-43. 10.1007/s00127-003-0596-5.

-

Griffiths P, Gossop M, Wickenden S, Dunworth J, Harris K, Lloyd C: A transcultural blueprint of drug use: qat (khat) in the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 1997, 170: 281-iv.

-

Poole R, Brabbins C: Drug induced psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1996, 168: 135-8.

-

Phillips P, Johnson South: How does drug and alcohol misuse develop amidst people with psychotic illness? A literature review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001, 36: 269-76. ten.1007/s001270170044.

-

Sato M, Numachi Y, Hamamura T: Relapse of paranoid psychotic land in methamphetamine model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992, 18: 115-22.

-

Mueser KT, Drake RE, Wallach MA: Dual diagnosis: a review of etiological theories. Aficionado Behav. 1998, 23: 717-34. 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00073-2.

-

Globe Wellness Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): Core version 2.ane Version 1.1. 1997, Geneva: World Wellness Organization

-

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Balderdash. 1987, xiii: 261-76.

-

Kay SR: Positive and negative syndromes in schizophrenia : assessment and research. 1991, New York: Brunner/Mazel

-

Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, Anker M, Korten A, Cooper JE, Twenty-four hour period R, Bertelsen A: Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and grade in unlike cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl. 1992, xx: 1-97.

-

Hambrecht M, Maurer Grand, Hafner H, Sartorius North: Transnational stability of gender differences in schizophrenia? An analysis based on the WHO written report on determinants of effect of severe mental disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992, 242: vi-12.

-

UNICEF: From perception to Reality. A study on child protection in Somalia. 2003, Nairobi: UNICEF Somalia

-

BK Lipska, ND Halim, PN Segal, DR Weinberger: Effects of reversible inactivation of the neonatal ventral hippocampus on behavior in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 2002, 22: 2835-42.

-

Farrell Thou, Boys A, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Coid J, Jenkins R, Lewis 1000, Meltzer H, Marsden J, Singleton Due north, et al: Psychosis and drug dependence: results from a national survey of prisoners. Br J Psychiatry. 2002, 181: 393-8. ten.1192/bjp.181.five.393.

-

Buhler B, Hambrecht Chiliad, Loffler W, an der Heiden W, Hafner H: Precipitation and determination of the onset and course of schizophrenia past substance abuse – a retrospective and prospective report of 232 population-based first disease episodes. Schizophr Res. 2002, 54: 243-51. 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00249-3.

-

Yui K, Ikemoto S, Goto Thousand, Nishijima Yard, Yoshino T, Ishiguro T: Spontaneous recurrence of methamphetamine-induced paranoid-hallucinatory states in female subjects: susceptibility to psychotic states and implications for relapse of schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002, 35: 62-71. 10.1055/s-2002-25067.

-

Saraceno B, Barbui C: Poverty and mental illness. Can J Psychiatry. 1997, 42: 285-90.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can exist accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/3/five/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to give thanks Mrs. Christine Klaschik and Dr. Rebecca Horn for their participation in the data drove and training of the interviewers.

The written report was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the European Community (Projection DECOSAC Sektor Project und EC DRP NW Somalia) and the High german Technical Cooperation (GTZ). Neither funding organizations influenced the design or acquit of the written report, the collection, management, analysis and estimation of the data, or the preparation, review and approving of the manuscript.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(south) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Development of the written report design and selection of instruments were accomplished by MO, FN, TE, MS, BR and HeH. MS, TE and MO performed airplane pilot studies. Training and supervision of local interviewers was provided by MO, HaH, FN and BL. Clinical interviews were conducted past MO, MS, CC and BL. Statistical analysis was performed by MO and TE. The article was equanimous and revised by MO, TE, BR, FN and HeH.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Nigh this article

Cite this article

Odenwald, M., Neuner, F., Schauer, Thousand. et al. Khat use equally risk cistron for psychotic disorders: A cantankerous-sectional and example-control study in Somalia. BMC Med 3, 5 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-3-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/1741-7015-3-5

Keywords

- Psychotic Symptom

- Psychotic Disorder

- Cathinone

- Positive Psychotic Symptom

- Khat Chewer

Source: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7015-3-5

0 Response to "Chronic Khat Use and Psychotic Disorders a Review of the Literature and Future Prospects"

Post a Comment